Team I Comparative Genomics Group: Difference between revisions

Lmckinney8 (talk | contribs) |

Lmckinney8 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 105: | Line 105: | ||

*** A smaller k-mer size could cause an increase in allele conflicts | *** A smaller k-mer size could cause an increase in allele conflicts | ||

*** When using raw reads, the tool sometimes cannot distinguish between true SNPs from sequencing errors | *** When using raw reads, the tool sometimes cannot distinguish between true SNPs from sequencing errors | ||

{| class="SNP Analysis Tool Search" | |||

|- | |||

!colspan="1"|Tool Name | |||

!colspan="1"|Year | |||

!colspan="1"|Based on | |||

!colspan="1"|Advantages | |||

!colspan="1"|Disadvantages | |||

|- | |||

|kSNP v. 3.0 | |||

|2015 | |||

|K-mer Analysis | |||

|Faster than multiple-alignment and reference-based methods. Has been tested on 68 genomes of E.coli | |||

|- | |||

|kSNP v. 3.0 | |||

|2015 | |||

|K-mer Analysis | |||

|Faster than multiple-alignment and reference-based methods. Has been tested on 68 genomes of E.coli | |||

|- | |||

|BactSNP | |||

|2019 | |||

|De-novo Assembly and Alignment Information | |||

|Can be run without a reference genome and has been benchmarked against other tools/pipelines for bacterial genomes | |||

|Doesn’t produce phylogenetic trees | |||

|- | |||

|ParSNP | |||

|2014 | |||

|Multiple genome alignment | |||

|Designed for microbial genomes. Avoids biases from mapping to a single reference | |||

|Cannot handle subset data, only works well for core genomes | |||

Not as sensitive as the other tools. | |||

Should be used in combination with a visualizer | |||

|- | |||

|RealPhy | |||

|2014 | |||

|Multiple reference sequence alignment | |||

|Avoids biases which come from using one reference genome | |||

|Requires a reference genome | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

[[File: kSNP3.png|400px|thumb|center|Figure X: kSNP3 workflow. (Gardner et al., 2013)]] | [[File: kSNP3.png|400px|thumb|center|Figure X: kSNP3 workflow. (Gardner et al., 2013)]] | ||

Revision as of 16:37, 13 April 2020

Team 1 Comparative Genomics

Team members: Heather Patrick, Lawrence McKinney, Laura Mora, Manasa Vegesna, Kenji Gerhardt, Hira Anis

Introduction and Objectives

Comparative genomics is a field in biomedical research in which the genomic features of different organisms are compared. In short, it involves the comparison of one genome to another. This type of comparative analysis can be utilized to discover what lies hidden within the sequences of genomes by comparing sequencing information. Comparative genomics has utilities in gene prediction, regulatory element prediction, phylogenomics, pharmacogenomics, pathogenicity and more. For the purposes of our analysis, we will employ comparative genomics tools to conduct an outbreak analysis. More specifically, we will compare bacterial genomes generated from Illumina next-generation sequence data to generate knowledge that will help us identify and characterize a bacterial outbreak strain of Escherichia coli (E. coli). Will will then apply our computational results to known biological insights and matched epidemiological to further characterize the identified bacterial strain. This data will be used to propose containment and treatment options that can be used by public health professional to address the foodbourne illness.

Our Data

- 50 isolates of Escherichia coli from an outbreak of foodborne illnesses. The genomes have been assembled and fully annotated.

- Epidemiological data consisting of: times, locations (states), and ingested foods of each case.

Our Bacteria

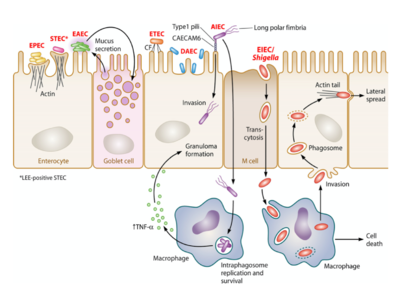

- E. coli is a gram-negative bacterium composed of numerous strains and serotypes (see Figure 1).

- E. coli contains plasmids (mobile genetic elements ) which generate genome diversity by promoting homologous recombination, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria, and can confer antimicrobial resistance and virulence.

- About ~46% of E. coli genome is conserved among all strains (core genome)

- E. coli occurs naturally in the lower part of the intestines of humans and warm-blooded animals, and under certain conditions, even commensal, “nonpathogenic” strains can cause infection.

- E. coli is typically transmitted through ingestion of contaminated food and water, person-to-person contact, contact with fomites.

- There are 8 types of pathogenic strains of E. coli (see Figure 2):

- Enteropathogenic E. coli(EPEC)

- Enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC)

- Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC)

- Enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC)

- Enterohamerrhagic E. coli (EHEC)

- Diffusely Adherent E. coli (DAEC)

- Adherent Invasive E. coli (AIEC)

- Shiga Toxin (Stx) producing Enteroaggregative E. coli (STEAEC)

- Strains representative of a pathotype contained shared genes as well as unique genes.

- Pathogenic E. coli is typically transmitted through ingestion of contaminated food and water, person-to-person contact, or contact with fomites. It typically invades and colonizes in the epithelium of the intestines.

E. coli Mobile Genetic Elements

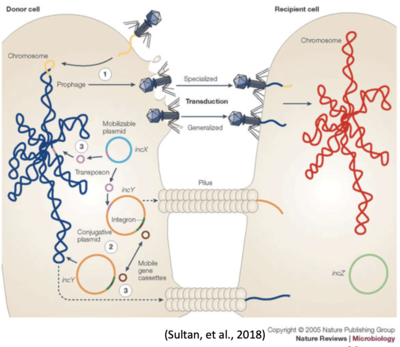

Bacterial cells transfer DNA between one another in three distinct ways (see Figure 3):

- Transduction (1)

- Conjugation (2)

- Transformation (3)

Transduction and conjugation depend on mobile genetic elements (MGEs), including most large plasmids and some bacteriophages. Pathogenomic analysis of the numerous plasmids present within representative strains of E. coli pathotypes (and commensal E. coli) has revealed considerable diversity and plasticity within these MGEs. Plasmids and bacteriophages play a major role in generating genome diversity by promoting homologous recombination and horizontal gene transfer between bacteria.

Team Objectives

- Compare and contrast functional & structural features of isolates.

- Antibiotic Resistance profile

- Virulence profile

- Differentiate outbreak vs. sporadic strains.

- Characterize the virulence and antibiotic resistance functional features of outbreak isolates.

- Identify the source and spread of the outbreak.

- Recommend outbreak response and treatment.

Methods

There are many ways to conduct comparative analysis on bacteria for the purposes of pathotyping/serotyping. We decided to perform analysis based on comparing bacterial genomes at different levels of resolution by discriminating our genome analysis at the whole genome level --> gene level --> SNP level. Detailed below are the tools and rationale for using the comparative genomics tools to achieve our research objectives.

WHOLE GENOME LEVEL ANALYSIS

- MUMmer v.04:

- A bioinformatic tool used align and compare entire genomes at varying evolutionary distances.

- It uses “Maximal Unique Matches” as pairwise anchor points to help improve the biological quality of the output alignments.

- Pros:

- Fast and efficient aligner

- Optimal for comparing two related bacterial strains

- Highly cited bioinformatics system in scientific literature (> 900 total citations; + 200 since 2018)

- Cons:

- Higher false alignment rate (FAR) when compared to similar tools.

GENE LEVEL ANALYSIS

- MLST: Multi Locus Sequence Typing

- A low-resolution classification to categorize different clonal expressions of pathogens into broad categories.

- The concept is based on allelic variation amongst highly conserved housekeeping genes (the schemes)

- The nomenclature is still widely used by clinicians and microbiologists

- There are bioinformatics tools that use raw sequence reads and others than use de novo assemblies.

- Three schemes available for Escherichia coli : Achtman,Pasteur, Whittam schemes (7:8:15)

- PubMLST ONLY USES Achtman and Pasteur

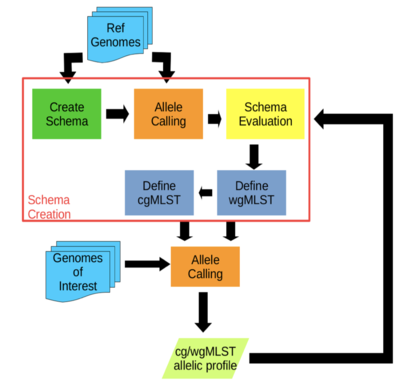

- chewBBACA:

- A comprehensive pipeline for the creation and validation of whole genome and core genome MLST schemas

- Schema creation and allele calls are done on complete or draft genomes resulting from de novo assemblers

- The allele calling algorithm is based on BLAST Score Ratio that can be run in multiprocessor settings

- Performs allele calling in a matter of seconds per strain

- Visualizes and evaluates allele variation in the loci

SNP LEVEL ANALYSIS

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms are mutations with a single DNA base substitution. When found in exonic regions, they can result in amino acid variants in the protein products or changes in protein length due to their effects on stop codons.

- Identification of SNPs across bacterial genomes is important for outbreak tracking, phylogenetic analysis and identifying strain differences that are important to phenotypes such as virulence and antibiotic resistance.

- Main Objective: Identify SNPs and produce a phylogenetic tree which will help us identify the source and strain of the organism causing the outbreak.

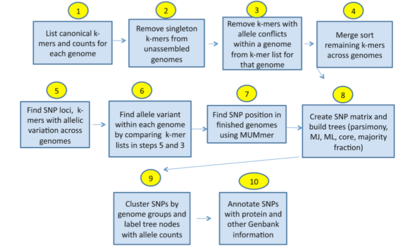

- kSNP3:

- Identifies all pan-genome SNPs in a set of given genome sequences and estimates phylogenetic trees based upon the identified SNPs.

- SNP identification is based on k-mer analysis

- kSNP builds Maximum Likelihood, Neighbor Joining and Parsimony Phylogenetic trees

- Doesn’t require a multiple sequence alignment or the selection of a reference genome

- SNPs are annotated from GenBank files.

- Pros:

- Has been tested on 68 finished E.coli genomes

- Can efficiently analyze distantly-related genomes

- Avoids biases stemming from the choice of a reference genome

- Finds SNPs which are present in core and non-core regions

- Cons:

- Cannot find SNPs that are too close to each other

- Using a bigger k-mer size will compromise the identification of high density SNPs

- A smaller k-mer size could cause an increase in allele conflicts

- When using raw reads, the tool sometimes cannot distinguish between true SNPs from sequencing errors

| Tool Name | Year | Based on | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| kSNP v. 3.0 | 2015 | K-mer Analysis | Faster than multiple-alignment and reference-based methods. Has been tested on 68 genomes of E.coli | |

| kSNP v. 3.0 | 2015 | K-mer Analysis | Faster than multiple-alignment and reference-based methods. Has been tested on 68 genomes of E.coli | |

| BactSNP | 2019 | De-novo Assembly and Alignment Information | Can be run without a reference genome and has been benchmarked against other tools/pipelines for bacterial genomes | Doesn’t produce phylogenetic trees |

| ParSNP | 2014 | Multiple genome alignment | Designed for microbial genomes. Avoids biases from mapping to a single reference | Cannot handle subset data, only works well for core genomes

Not as sensitive as the other tools. Should be used in combination with a visualizer |

| RealPhy | 2014 | Multiple reference sequence alignment | Avoids biases which come from using one reference genome | Requires a reference genome |

Results

Conclusion

Treatment Recommendation

Outbreak Response Recommendation

Recommended Classes of Antibiotics for Physicians to Prescribe

Classes of Antibiotics for Physicians to Avoid

In-Class Presentations

- Comparative Genomics Background and Strategy:

- Comparative Genomics Final Results:

References

- Chen X, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhao Y, Sun C, Yang M, Wang J, Liu Q, Zhang B, Chen M, Yu J, Wu J, Jin Z and Xiao J (2018) PGAweb: A Web Server for Bacterial Pan-Genome Analysis. Front. Microbiol. 9:1910. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01910

- Maiden MC, Jansen van Rensburg MJ, Bray JE, et al. MLST revisited: the gene-by-gene approach to bacterial genomics. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11(10):728-36.

- Marçais G, Delcher AL, Phillippy AM, Coston R, Salzberg SL, et al. (2018) MUMmer4: A fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLOS Computational Biology 14(1): e1005944. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005944

- Perez-Losada M, Arenas M, Castro-Nallar E. Microbial sequence typing in the genomic era. Infection, Genetics and Evolution. 2018;63:346-359. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2017.09.022

- Strockbine N, Bopp C, Fields P, Kaper J, Nataro J. 2015. Escherichia, Shigella, and Salmonella, p 685-713. In Jorgensen J, Pfaller M, Carroll K, Funke G, Landry M, Richter S, Warnock D (ed), Manual of Clinical Microbiology, Eleventh Edition. ASM Press, Washington, DC. doi: 10.1128/9781555817381.ch37

- Sultan, I., Rahman, S., Jan, A. T., Siddiqui, M. T., Mondal, A. H., & Haq, Q. M. R. (2018). Antibiotics, Resistome and Resistance Mechanisms: A Bacterial Perspective. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9(2066). doi:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02066

- Trees E, Rota P, Maccannell D, Gerner-smidt P.. Molecular Epidemiology, p 131-159. In Jorgensen J, Pfaller M, Carroll K, Funke G, Landry M, Richter S, Warnock D (ed), Manual of Clinical Microbiology, Eleventh Edition. ASM Press, Washington, DC. 2015. doi: 10.1128/9781555817381.ch10