Team I Genome Assembly Group: Difference between revisions

Lmckinney8 (talk | contribs) |

Lmckinney8 (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

4. To send off the highest quality result to the gene prediction team. | 4. To send off the highest quality result to the gene prediction team. | ||

** [https://compgenomics2020.biosci.gatech.edu/index.php?title=Team_I_Gene_Prediction_Group&action=edit&redlink=1 Team 1 | Genome Prediction] | |||

== '''Methods''' == | == '''Methods''' == | ||

Revision as of 17:53, 16 February 2020

Team 1 Genome Assembly

Team members: Lawrence McKinney, Laura Mora, Jessica Mulligan, Heather Patrick, Devishi Kesar, and Cecilia (Hyeonjeong) Cheon

Introduction

In bioinformatics, sequence assembly of a genome is the first of many steps involved to identify and characterize an organism. It may be considered the most important step in the stages of analysis and interpretation (see below) because of the challenge that persist concerning high quality genome assembly and annotation [4].

The basic principle of assembly principle of assembly is to note that the more similarity that exists between the end of one read and the beginning of another, the more likely they are to have originated from overlapping stretches of the genome. The output of an assembly is typically a set of ‘‘contigs,’’ which are contiguous sequence fragments, ordered and oriented into ‘‘scaffold’’ sequences, with gaps between contigs within scaffolds representing regions of uncertainty. There are numerous subclasses of assembly problems that can be distinguished by, among other things, the nature of: (1) the reads, (2) the types of sequences being assembled, and (3) The availability of homologous (related) and previously assembled sequences, such as a reference genome or the genome of a closely related species.

Using the most relevant and high-quality tools are important for performing comparative genomics. Importantly, results may have implications in public health that may affect many lives. For the purposes of our project, we are tasked with identifying the source/origin of a given food-borne illness.

Stages of analysis and interpretation of data

1 - genome assembly 2 - gene prediction 3 - functional annotation 4 - comparative genomics 5 - production of a predictive webserver

Figure 1. Genome Assembly Overview (https://www.nature.com/articles/nmeth.1935#citeas)

Team Goals

1. To perform quality control on reads before and after assembling the genome:

Before:

After:

2. To evaluate the performance of assembly tools:

3. To use the best tool to perform de novo assembly based on the 50 isolates.

4. To send off the highest quality result to the gene prediction team.

Methods

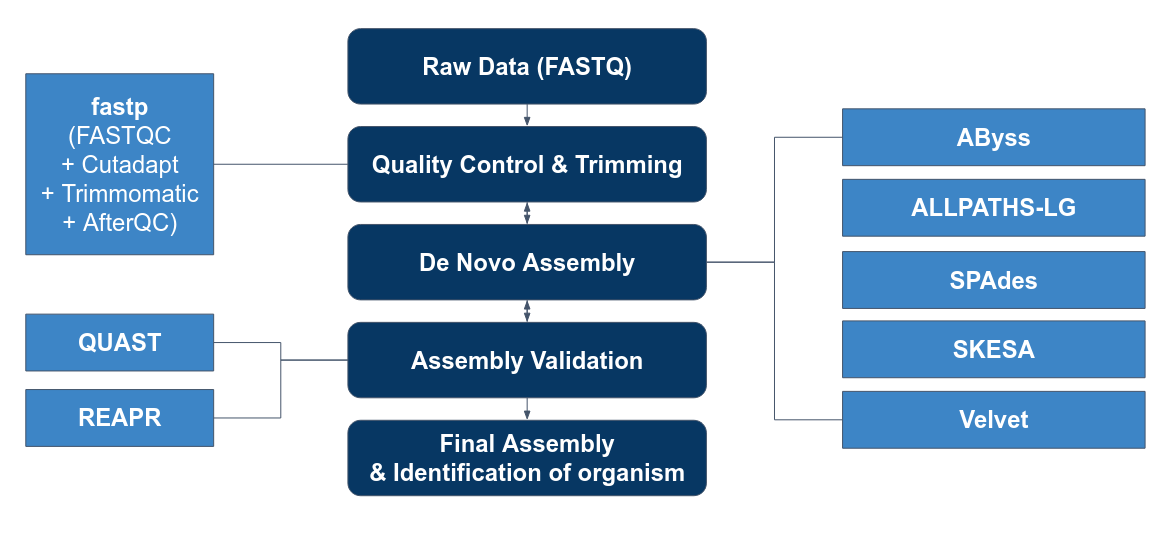

Initial Genome Assembly Pipeline

Raw Data

Our team as assigned 50 isolates all in FASTQ format. FASTQ is a standard format that contains the read sequence and a quality for every base.

Quality Control & Trimming

It is important to check quality of sequences prior to proceeding to assembly including checking the quality of the average base quality score per read, the GC content distribution and identification of the most duplicated reads. Proceeding with assembly of the sequences without checking for the quality of the reads will lead the misinterpretation of results. For the purposes of our project we will be using fastp() for quality control analysis as well as read trimming. We will use Fastp because it includes most features of similar tools used for quality control and trimming (including FASTQC + Cutadapt + Trimmomatic + AfterQC), all while running 2 to 5 times faster than any of them alone.

- Our threshold Minimum quality score: 20

- Our Sliding window: 10

- We will trim reads from both ends

Assembly

An important decision when approaching the assembly stage of assembling a genome is to determine whether to perform assembly via a reference genome or performing de novo assembly. Reference assembly refers to aligning the sequences to a known genome. De novo assembly refers to aligning the sequences via overlapping groups called contigs to build a novel genome. There are pros and cons to each approaches. For assembly to a reference genome, the assembly can be done relatively quickly. It is also good for single nucleotide variants (SNV) and small indels. However the reference genome approach is limited length for feature detection and requires a reference that is close to the sequenced data. The de novo assembly approach is good for completely new sequences not present in the reference. However it can be slow and has high infrastructure requirements and is bad at hiding raw data limitations.

It is important to understand characteristics of the biological data you are working with to make certain decisions when deciding to use a bioinformatic tool. The genome used for our project is not human and likely prokaryotic (due to basepair count). Unlike the human genome, that is about 99.9% the same across species, bacterial and viral genomes can change rapidly making the approach of genomic assembly via a reference genome not optimal due to the potential loss of information when mapping occurs. For this reasons, we will proceed in assembling the genome using the de novo assembly approach.

de Novo Assembly

De novo assembly is the most common type of genome assembly for short read sequences. It involves reconstructing entire genome from overlapping sequence reads. The quality depends on the size of the reads and number of gaps between them. Most tools use either de Bruijn graphs (Eulerian) or Overlap graphs (Hamiltonian) as their algorithms. De novo assembly can generate new and accurate reference sequences, even for complex genomes.

Rationale for (Assembler) tool selection

Based on literature that provide an unbiased assessment of pro/cons of various genome assembly tools.

- GAGE (Genome Assembly Gold-standard Evaluations)

- A study designed to provide a snapshot of how the latest genome assemblers compare on a sample of large-scale next-generation sequencing projects.

- Helps to answer questions like: Which assembly software will produce the best results?

- GAGE (Genome Assembly Gold-standard Evaluations)

- Assemblathon I

- A (critical) competitive assessment of de novo short read assembly methods.

- Aims to comprehensively assess the state of the art in de novo assembly methods when applied to current sequencing technologies.

- Assemblathon I

Assembly Validation

It is generally the case that the right answer to an assembly problem is unknown. Understandably therefore, common methods for assessing assembly quality are needed.

QUAST

Quast is a quality assessment tool used for genome assembly [1].

Final Genome Assembly Pipeline

Results

Conclusion

In-Class Presentations

File:Team 1 Genome Assembly Presentation 1.pdf

References

1. Alexey Gurevich, Vladislav Saveliev, Nikolay Vyahhi, Glenn Tesler, QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies, Bioinformatics, Volume 29, Issue 8, 15 April 2013, Pages 1072–1075, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086

2. Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19(5):455–477. doi:10.1089/cmb.2012.0021

3. Butler, Jonathan et al. “ALLPATHS: de novo assembly of whole-genome shotgun microreads.” Genome research vol. 18,5 (2008): 810-20. doi:10.1101/gr.7337908

4. Earl, Dent et al. “Assemblathon 1: a competitive assessment of de novo short read assembly methods.” Genome research vol. 21,12 (2011): 2224-41. doi:10.1101/gr.126599.111

5. Maccallum, Iain et al. “ALLPATHS 2: small genomes assembled accurately and with high continuity from short paired reads.” Genome biology vol. 10,10 (2009): R103. doi:10.1186/gb-2009-10-10-r103

6. Miller, Jason R et al. “Assembly algorithms for next-generation sequencing data.” Genomics vol. 95,6 (2010): 315-27. doi:10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.03.001

7. Pritt, J., Chen, N. & Langmead, B. FORGe: prioritizing variants for graph genomes. Genome Biol 19, 220 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-018-1595-x

8. Quainoo, S., Coolen, J.P., Hijum, S.A., Huynen, M.A., Melchers, W.J., Schaik, W.V., & Wertheim, H.F. (2017). Whole-Genome Sequencing of Bacterial Pathogens: the Future of Nosocomial Outbreak Analysis. Clinical microbiology reviews, 30 4, 1015-1063 .

9. Rahman, A., Pachter, L. CGAL: computing genome assembly likelihoods. Genome Biol 14, R8 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2013-14-1-r8

10. Salzberg, Steven L et al. “GAGE: A critical evaluation of genome assemblies and assembly algorithms.” Genome research vol. 22,3 (2012): 557-67. doi:10.1101/gr.131383.111

11. Shifu Chen, Yanqing Zhou, Yaru Chen, Jia Gu; fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor, Bioinformatics, Volume 34, Issue 17, 1 September 2018, Pages i884–i890, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560

12. Sohn, Jang-il; Nam, Jin-Wu. “The present and future of de novo whole-genome assembly”, Briefings in Bioinformatics, Vol 19.1 (2018). doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbw096

13. Souvorov A., Agarwala R., & Lipman D.J. SKESA: strategic k-mer extension for scrupulous assemblies. Genome Biology. 2018; 19(1). doi:10.1186/s13059-018-1540-z

14. Tanja Magoc, Stephan Pabinger, Stefan Canzar, Xinyue Liu, Qi Su, Daniela Puiu, Luke J. Tallon, Steven L. Salzberg, GAGE-B: an evaluation of genome assemblers for bacterial organisms, Bioinformatics, Volume 29, Issue 14, 15 July 2013, Pages 1718–1725, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btt273

15. Zerbino, D., & Birney, E. (n.d.). Velvet: de novo assembly using very short reads. Hinxton: European Bioinformatics Institute.