Team II Comparative Genomics Group: Difference between revisions

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

=== '''1.3 Tools and Algorithms ''' === | === '''1.3 Tools and Algorithms ''' === | ||

=== | === '''1.3.1 Alignment based tools ''' === | ||

* ANIb and ANIm | |||

ANIb and ANIm represent blast-blast ANI and MUMer-based ANI. They are both one way ANI, without reciprocal search. Popular software includes JSpecies, java based ANI calculation. JSpecies is a friendly UI interface but cannot be used to calculate large datasets. | |||

* Reciprocal ANIb and ANIm | |||

Reciprocal ANIb and ANIm are the most popular ANI calculation method. Tools such as ani.rb and OrthANI, which are ruby and java based, respectively. Both ani.rb and OrthANI ani.rb can be used to calculate pairwise ANI for datasets with thousands of genomes. ani.rb is blast-based while OrthANI can use 3 different method such as blast, MUMer and usearch (usearch_local). | |||

=== ''' MLST ''' === | === ''' MLST ''' === | ||

Revision as of 12:41, 28 March 2020

Team 2: Comparative Genomics

Team Members: Kara Keun Lee, Courtney Astore, Kristine Lacek, Ujani Hazra, Jayson Chao

Class Presentations

Introduction

What is Comparative Genomics?

Once genomes are fully assembled and annotated, outbreak analysis can begin via comparative genomics. Generally, metadata ascertained from gene prediction and annotation can be used to map the relatedness of multiple isolates. Combined with epidemiological data, a given outbreak can be mapped back to a particular source (patient zero) and tracked to determine which strains are outbreak isolates and which are sporadic cases. Furthermore, phenotypic features such as virulence, antibiotic resistance, and pathogenicity can be determined. Compilation of these data allows for recommendations to be made on behalf of human impact, treatment strategy, and management methods to address further spread.

Our Data

- Our genomic data comes from 50 isolates of C. jejuni from an outbreak of foodborne illnesses. The genomes are assembled and fully annotated.

- Our epidemiological data include times, locations, and ingested foods of each case.

Pipeline Overview

Objectives

- Identify kinds of strains (outbreak vs. sporadic)

- Construct phylogeny demonstrating which isolates are related and which differ

- Determine the source of the outbreak

- Map virulence and antibiotic resistance features of outbreak isolates

- Compile recommendations for outbreak response and treatment

Overview of Techniques

When performing phylogenomics, there are many options by which one can classify similarities and differences across the genome. Our approach utilizes tools from three different techniques.

ANI

1.1 Definition

Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) is a measure of nucleotide-level genomic similarity between the coding regions of two genomes. A value of 70 % DDH (DNA-DNA hybridization, 1 kb fragments of genome) was proposed as a recommended standard for delineating species and it is a golden standard for species definition based on hybridization experiment. A 95% percent ANI corresponds to 70 % DDH in a study combining experiment hybridization and bioinformatic analysis of bacterial genomes.

1.2 How to calculate

Calculating ANI usually involves the fragmentation of genome sequences, followed by nucleotide sequence search, alignment, and identity calculation. The original algorithm to calculate ANI used the BLAST program as its search engine. As it is done in the hybridization experiment, one genome (query genome) will be chopped in to 1 kb fragments when comparing two genomes using bioinformatic tools. Then each of those 1 kb fragments will be search against genome B using blast or other local alignment tools (search for example). Then the identity of each 1 kb fragment will be calculated. The average identity value of those fragments will be used as ANI.

A reciprocal search of genome B against genome A was then proposed to be more reliable and accurate, which is also called orthlogous ANI.

1.3 Tools and Algorithms

1.3.1 Alignment based tools

- ANIb and ANIm

ANIb and ANIm represent blast-blast ANI and MUMer-based ANI. They are both one way ANI, without reciprocal search. Popular software includes JSpecies, java based ANI calculation. JSpecies is a friendly UI interface but cannot be used to calculate large datasets.

- Reciprocal ANIb and ANIm

Reciprocal ANIb and ANIm are the most popular ANI calculation method. Tools such as ani.rb and OrthANI, which are ruby and java based, respectively. Both ani.rb and OrthANI ani.rb can be used to calculate pairwise ANI for datasets with thousands of genomes. ani.rb is blast-based while OrthANI can use 3 different method such as blast, MUMer and usearch (usearch_local).

MLST

MLST or Multi-locus Sequence Typing identifies a set of loci (housekeeping genes) in the genome and compares each locus in a genome against the set of loci. It estimates the relationships between bacteria based on allelic variations in specific loci than their nucleotide sequences. MLST data can be used to investigate evolutionary relationships among bacteria. However, the sequence conservation of the housekeeping genes limits the discriminatory power of MLST in differentiating bacterial strains.

There are several types of MLST:

Whole-genome MLST (wgMLST): All loci of a given isolate compared to equivalent loci in other isolates (typing scheme based on a few thousand genes).

- Creates wgMLST tree (different styles exist)

- Minimum spanning tree = circles with sizes indicative of the frequency of ST and distance showed on connecting lines

Core-genome MLST (cgMLST): Focused on only the core elements of the genomes of a group of bacteria (typing scheme based on a few hundred genes).

7-Gene MLST: Chooses 7 loci in the genome and compare all genomes to these 7 loci.

- Profile of alleles (“sequence type” or ST) by calling the alleles

- Genome assembly optional – there are assembly free methods

- Creates a phylogeny

Ribosomal MLST (rMLST): Based on 53 loci that code for ribosomal proteins present in most bacteria.

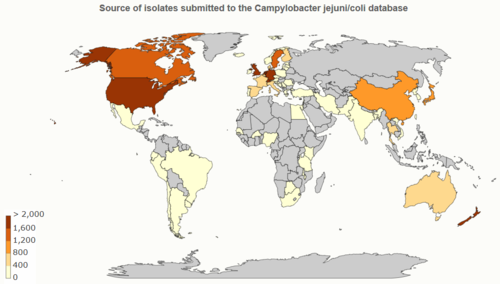

Database: PubMLST

PubMLST (Public databases for molecular typing and microbial genome diversity) for Campylobacter jejuni/coli (as of 17MAR2020):

- 98,017 isolates

- 50,138 genomes

- 1,286,733 alleles

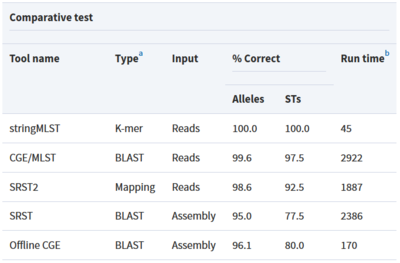

Tool: stringMLST

stringMLST is a tool for detecting the MLST of an isolate directly from the genome sequencing reads.

- Predicts the ST of an isolate in a complete assembly and alignment-free manner

- Downloads and builds databases from pubMLST using the most recent allele and profile definitions

- Faster algorithm compared to traditional MLST tools that maintain high accuracy

Tool: MentaLiST

A k-mer based MLST caller designed specifically for handling large MLST schemes.

- Capable of dealing with MLST schemes with up to thousands of genes while requiring limited computational resources

- MLST calling that does not require pre-assembled genomes, working directly with the raw WGS data, and also avoids costly pre-processing steps (i.e. contig assembly or read mapping onto a reference)

- Follows the general principle of k-mer counting, introduced in stringMLST, with some data compression improvements that lead to much smaller database sizes and a faster running time

Tool: ARIBA

Assembly based tool, primarily developed for identifying Anti-Microbial Resistance - associated genes and single nucleotide polymorphisms directly from short reads

- Provides inbuilt support for and functionality for multi-locus sequence typing (MLST) using data from PubMLST

- Provides inbuilt support for PlasmidFinder and VFDB (Virulence Factor Databases)

- Can be used in the study of Virulence Profile and AMR features along with the results from the Functional Annotation group

SNP Typing

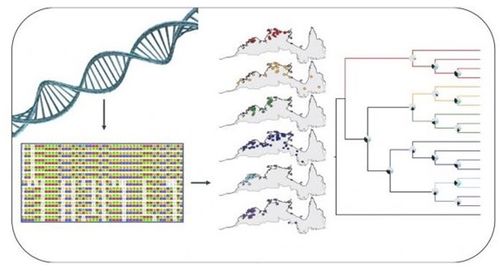

SNP stands for Single Nucleotide Polymorphism, meaning that certain alleles have two or three possibilities as to which base is at a given locus. As SNPs accumulate through de novo mutations and are passed down through generations, comparing a given isolate's SNPs to other isolates and a reference genome allow ascertainment of phylogenetic distance between samples(1). Tools have been developed to compare bases position by position (SNP-calling) and create matrices to compute relatedness between samples based on common SNPs.

Generalized Algorithm Overview:

- Pre-processing and read cleaning

- Mapping

- SNP calling against a reference genome

- Phylogeny generation based on SNP profiles

Tools to be tested:

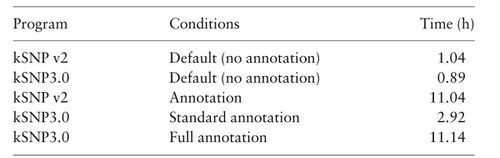

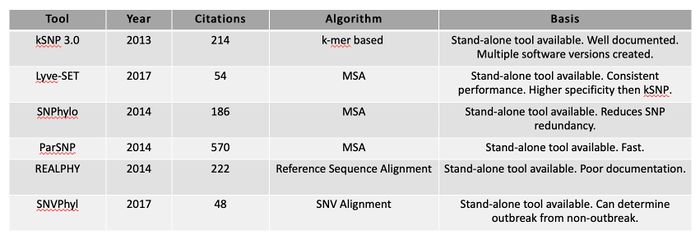

Tool: kSNP3.0

- Optimal for situations where whole genome alignments don't work

- k-mer-based approaches are alignment-free and have a faster runtime

- Multiple kSNP versions have been created and thoroughly tested

Tool: Lyve-SET

- MSA-based approach (computationally expensive)

- Consistent performance according to literature

- Has a higher sensitivity, specificity, and average Sn and Sp than kSNP

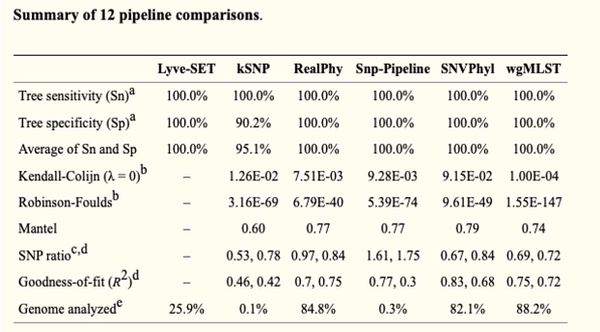

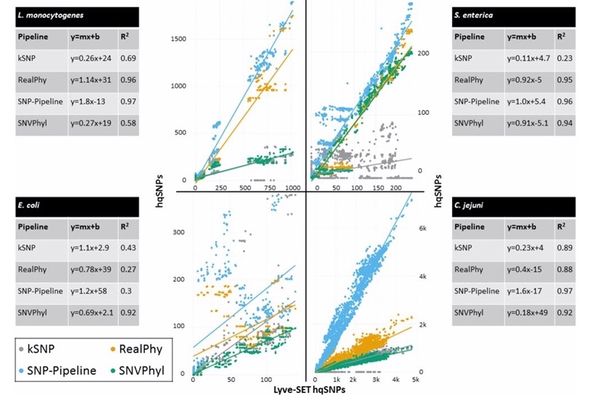

Table: SNP-based tool comparison

Outbreak Analysis Results

Preventative Measures

- Identify food source of outbreak strains to recommend recalls

- Determine potential water source shutdown

- Create PSAs to alert public of risks and hygienic prevention

Outbreak Response

- Analyze date distribution / geographic outbreak plots

- Refer related cases to physicians for treatment

- Alert state labs of heightened related cases

- Investigate supply chain correlations for specific product

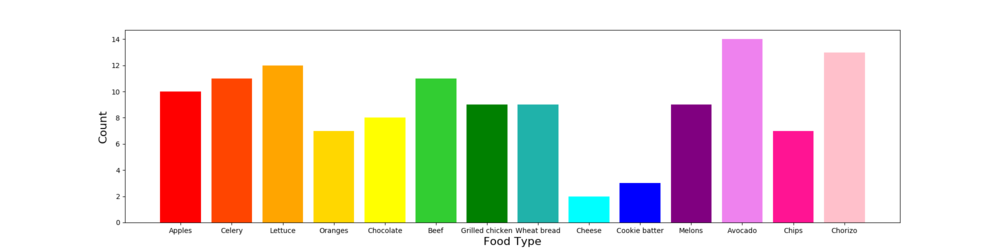

Figure: Date distribution

Figure: Frequency of different food types across samples.

Source of Outbreak

Human Impact

Treatment Strategy

- Determination of antibiotics that will be most effective and ineffective from AMR profile

CDC Recommendations

Works Cited

1. Touchman, J. (2010). "Comparative Genomics". Nature Education Knowledge. 3 (10): 13.

2. Xia, X. (2013). Comparative Genomics. SpringerBriefs in Genetics. Heidelberg: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-37146-2. ISBN 978-3-642-37145-5.

3. Goris, J., Konstantinidis, K. T., Klappenbach, J. A., Coenye, T., Vandamme, P., & Tiedje, J. M. (2007). DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole- genome sequence similarities. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Mi- crobiology, 57, 81–91

4. Konstantinidis, K. T., & Tiedje, J. M. (2005). Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 102, 2567–2572.

5. Arahal, D.R. (2014). Whole-genome analyses: average nucleotide identity. In: Methods in microbiology. Elsevier, pp. 103-122.

6. Richter, M., & Rossello ́-Mo ́ra, R. (2009). Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 106, 19126–19131.

7. Varghese, N.J., Mukherjee, S., Konstantinidis, K.T. & Mavrommatis, K. (2015) Microbial species delineation using whole genome sequences. Nucleic Acid Research, 43, 6761–6771.

8. Wayne, L. G., Brenner, D. J., Colwell, R. R., Grimont, P. A. D., Kandler, O., Krichevsky, M. I., Moore, L. H., Moore, W. E. C., Murray, R. G. E. & other authors (1987). International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology. Report of the ad hoc committee on reconciliation of approaches to bacterial systematics. Int J Syst Bacteriol 37, 463–464.

9. Jain, C., Dilthey, A., Koren, S., Aluru, S. & Phillippy, A. M. A fast approximate algorithm for mapping long reads to large reference databases. In International Conference on Research in Computational Molecular Biology (Springer, Hong Kong, 2017).

10. https://www.applied-maths.com/applications/mlst

11. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5472909/

12. https://pubmlst.org/campylobacter/

13. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5610716/

14. https://academic.oup.com/bioinformatics/article/33/1/119/2525695

15. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5857373/

16. Lee, T., Guo, H., Wang, X. et al. SNPhylo: a pipeline to construct a phylogenetic tree from huge SNP data. BMC Genomics 15, 162 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-15-162

17. Katz, Lee S et al. “A Comparative Analysis of the Lyve-SET Phylogenomics Pipeline for Genomic Epidemiology of Foodborne Pathogens.” Frontiers in microbiology vol. 8 375. 13 Mar. 2017, doi:10.3389/fmicb.2017.00375

18. Shea N Gardner, Tom Slezak, Barry G. Hall, kSNP3.0: SNP detection and phylogenetic analysis of genomes without genome alignment or reference genome, Bioinformatics, Volume 31, Issue 17, 1 September 2015, Pages 2877–2878, https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btv271

19. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6737581/#!po=11.3636

20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5243249/

21. https://www.cdc.gov/foodsafety/outbreaks/investigating-outbreaks/index.html